The Rebbe and the RAV

The Rebbe and the Rav: Two remarkable Torah leaders and their relationship

The Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, and the Rav, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, of righteous memory, were heirs to two traditions that are largely defined in contrast and in correspondence to one another. But each draw from the tradition of the other, and their personal relationship ran deep.

https://jewishaction.com/jewish-world/people/rebbe-rav/

Perhaps there was also a basic subliminal thought behind the Rav’s participation. He was expressing his gratitude to Chabad for the additional Torah perspectives they set in motion for him. In a talk he delivered at Lincoln Square Synagogue in 1975, the Rav related:

By sheer association I recall an experience from my early youth. Let me give you the background of that experience.

I was then about seven or eight years old. I attended a heder in a small town on the border of White Russia and Russia proper. The town was called Khaslavichy; you certainly have never heard of it. My father was the rabbi in the town. I, like every other Jewish boy, attended the heder. My teacher was not a great scholar, but he was [a] hasid, a Habbadnik [a follower of the Lubavitcher Rebbe]. His expertise in the study and teaching of Talmud was then under a question mark. As a young boy, I too questioned his scholarship. I know now that he was not a great scholar.

The account of this farbrengen quickly circulated throughout the Torah world. For many, it was an ecstatic moment that the Rav and the Rebbe could publicly exemplify the Talmudic aphorism that “the disciples of the sages increase peace in the world” (Berachot 64a). This was particularly on target at this event as both protagonists descended from families that represented different configurations of Torah civilization.

_________________________________________________________________________

1. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Vol. I (New Jersey, 1999), 23-24 and Shulamith Soloveitchik Meiselman, The Soloveitchik Heritage: A Daughter’s Memoir (New Jersey, 1995), 124-125

______________________________________________________________________

There was a knock on the door when I was visiting my rebbe, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, to express my condolences upon the loss of his mother. It was 1967.

It was quite early and I was the only one with the Rav at that moment. I quickly opened the door to the apartment and was greeted by two patriarchal figures, Rabbis Yochanan Gordon and Yisroel Jacobson. I ushered them in and observed the Rav’s face brighten as they entered. They informed my rebbe that they were sent by the Lubavitcher Rebbe to convey his condolences on the Rav’s bereavement. They were soon engaged in animated conversation about Lubavitch in the “Alter Heim” (“Old Country”). They discussed the Rav’s formative years in Khaslavichy, White Russia, where his father, Reb Moshe, was the rabbi. The Khaslavichy Jewish community consisted of a large number of Lubavitch Chassidim, and here the young Soloveitchik was exposed to Chabad Chassidic literature and lifestyle. Their influence remained with the Rav for the rest of his life.1 1. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Vol. I (New Jersey, 1999), 23-24 and Shulamith Soloveitchik Meiselman, The Soloveitchik Heritage: A Daughter’s Memoir (New Jersey, 1995), 124-125.

When the Chabad emissaries left, the Rav turned to me and reminisced about the years he spent studying at the University of Berlin, where he first met the future seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. With a sense of admiration, the Rav said to me, “At the University, no one knew about my background and where I was coming from. Everyone knew who the future Lubavitcher Rebbe was!” Years later, I came across pictures of the Rav and the Rebbe during their Berlin days. My rebbe’s appearance was similar to that of most other students, while the Lubavitcher Rebbe attended university in Chassidic garb.

A student of the Rav discussed the Berlin era with him at a later period. This student later recapped what the Rav recounted:

The Rav was already in the University of Berlin when the Lubavitcher Rebbe first came there. The Rav showed him the ropes when he arrived, and introduced him to R. Chaim’s derech in learning. The Lubavitcher Rebbe was a very quiet person during those years.22. David Holzer, The Rav: Thinking Aloud

(Florida, 2009), 42

The Rav was introduced to the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, when the latter visited his son-in-law in Berlin in 1929 and 1930. Rabbi Schneersohn wrote:

Regarding Rabbi Y. Soloveitchik, I know him already for many years. While he was still in Berlin, I was introduced to him by my son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. My son-in-law told me about his great in-depth understanding of Torah and how he studies assiduously. I was very delighted to become close to him . . . 3

3. Cited by Shaul Shimon Deutsch, Larger Than Life: The Life and Times of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Vol. II (Brooklyn, 1997), 113.

In 1941, the relationship between the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe and the Rav was helpful in enabling my rebbe to succeed his father, Rav Moshe Soloveichik, as the senior rosh yeshivah at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn sent a letter of support for the Rav, which greatly enhanced his candidacy. It read:

It is my hope that the great, excellent, and renowned gaon, Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik, will be selected to sit on his father’s chair as the rosh yeshivah of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. It is only fitting and proper that he inherit this position. He will bring abundant blessings to the Yeshiva after the recent loss of its two heads. The eminent gaon has the ability to restore the school’s former glory and through him solace will be attained.44. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Silver Era: Rabbi Eliezer Silver And His Generation (Jerusalem, 2000), 270

A member of the Rav’s immediate family declared that this communication was pivotal in the Rav being selected to replace his late father. Dr. Haym Soloveitchik related:

In fact, the Previous Rebbe was ultimately the deciding factor in my father getting the job. The committee was split in their opinion about my father. One of the members of the committee was Mr. Abraham Mazer, a well-known New York philanthropist. He was also a very big supporter of Lubavitch. The Previous Rebbe called Mr. Mazer and asked him to support my father. His vote was the key factor in the committee’s decision to offer my father the job.55. Cited by Deutsch, Larger Than Life, II, 116.

The Rav was able to publicly affirm his esteem for Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn shortly afterwards. On June 14, 1942, at a banquet celebrating the founding of the United Lubavitcher Yeshivoth in the United States, the keynote address was delivered by the Rav. In his speech, he compared the Rebbe to the first-century Tanna, Rav Chanina ben Dosa. Rabbi Soloveitchik cited the Talmudic passage which described one of the miracles that occurred for Rav Chanina ben Dosa:.

Once on a Friday eve he noticed that his daughter was sad, and he said to her, “My daughter, why are you sad?” She replied, “My oil can got mixed up with my vinegar can and I kindled of it the Sabbath light.” He said to her, “Why should this trouble you? He who had commanded the oil to burn will also command the vinegar to burn.” A Tanna taught: “The light continued to burn the whole day until they took of it light for the Havdalah” (Ta’anit 25a).

The Rav declared that Lubavitch Chassidism, under the guidance of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, had also successfully demonstrated that vinegar can burn. Despite the obstacles engendered by the Godless Communist regime, Lubavitch Chassidism continued to function throughout the Russian realm. Similarly, the Rav was confident that the Lubavitch movement could succeed in kindling the flames of Torah in the United States. Despite the spirituality impoverished American soil, the vinegar would burn.66. Shalom Dover HaLevi Wolpo, Shemen Sasson Meichaveirecha, Vol. III (Holon, 2003), 178-179.

During this period, both the Rav and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who was now the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, became active on the American Torah educational scene. Rabbi Soloveitchik succeeded his father as the senior rosh yeshivah in May of 1941. He remained in this position until illness forced his retirement in December of 1985.

The Rebbe arrived in the United States on June 23, 1941. He quickly became instrumental in the establishment of two central Lubavitch organizations: Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch (Central Organization for Jewish Education) and Machne Israel, a social service agency. Following his father-in-law’s death in 1950, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson reluctantly assumed leadership of the movement.7 In the ensuing decades, the Rav and the Rebbe maintained an indirect but ongoing relationship. They corresponded before the High Holy Days and the yamim tovim.8 In 1964, when the Rebbe sat shivah for his mother, Rebbetzin Chana, he was visited by Rav Soloveitchik. The two scholars soon engaged in a learned discussion of the Sabbath and Festival status of the mourner before the burial (aninut). This exchange evolved from the Rebbetzin’s death on Shabbat. The Rebbe later wrote to the Rav, detailing his stance and his understanding of Maimonides’ commentary on this topic.9

The Rav was accompanied to the shivah by Rabbi Sholem Kowalsky. The latter transcribed his conversation with the Rav as they traveled to Crown Heights. Rabbi Kowalsky wrote:

The journey from Yeshiva University to Crown Heights took over an hour, affording me lots of time to discuss the Lubavitcher Rebbe with the Rav. During the discussion, I asked the Rav to tell me about the Lubavitcher Rebbe as a person—his imposing character, his personality and his great Torah scholarship, as well as his relationship with him.

The Rav told me that he was a great admirer of the Rebbe. He said their relationship began when they were in Berlin where they were both studying at the University of Berlin. During that period they would often meet at the home of the Gaon, Rabbi Chaim Heller. It was in the course of these meetings that a strong friendship developed between the two men, both of whom were destined to become outstanding spiritual leaders of the century.

The Rav recalled that the Rebbe always carried the key to the mikvah with him when he attended lectures at the university. “At about two or three o’clock every afternoon when he left the university, he would go straight to the mikvah. No one was aware of the minhag and I only learnt about it by chance,” the Rav said.

“On another occasion, I offered the Rebbe a drink. The Rebbe refused, but when I pressured him I understood that he was fasting that day. It was Monday and the Rebbe was fasting. Imagine that,” Rabbi Soloveitchik said to me. “A Berlin University student immersed in secular studies maintains this custom of mikvah and fasting.

“These things made huge impressions on me. Additionally, the Rebbe had an amazing memory.” The Rav described the Rebbe’s memory as “gevaldig” (astounding). “In all my life, I never encountered someone with such a memory.”

Then the Rav proceeded to describe his understanding of the Rebbe’s Torah.

“Those of us who emanate from Brisk don’t adhere to the pilpul system perpetuated in Poland,” the Rav said, “but the Rebbe has a gevaldiger comprehension of the Torah.

________________________________________________________________________

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (January 2017)

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

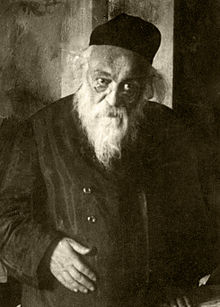

| Chaim Soloveitchik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Reb Chaim Brisker 1853 Volozhin, Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 July 1918 (aged 64–65) Otwock, Kingdom of Poland |

Chaim (Halevi) Soloveitchik (Yiddish: חיים סאָלאָווייטשיק, Polish: Chaim Sołowiejczyk), also known as Reb Chaim Brisker (1853 – 30 July 1918), was a rabbi and Talmudic scholar credited as the founder of the popular Brisker approach to Talmudic study within Judaism. He was born in Volozhin in 1853, where his father, Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik served as a lecturer in the famous Volozhiner Yeshiva. After a few years, his father was appointed as a Rav in Slutzk, where young Chaim was first educated. While still a youngster, his genius and lightning-quick grasp were widely recognized. Eventually, following many years as a senior lecturer in the renowned Volozhiner Yeshiva, he accepted a position as Rav of Brest, Belarus (Brisk in Yiddish).[1] A member of the Soloveitchik-family rabbinical dynasty, he is commonly known as Reb Chaim Brisker ("Rabbi Chaim [from] Brisk").

He is considered the founder of the "Brisker method" (in Yiddish: Brisker derech; Hebrew: derekh brisk), a method of highly exacting and analytical Talmudical study that focuses on precise definition/s and categorization/s of Jewish law as commanded in the Torah with particular emphasis on the legal writings of Maimonides.

His primary work was Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim, a volume of insights on Maimonides' Mishneh Torah which often would suggest novel understandings of the Talmud as well. Based on his teachings and lectures, his students wrote down his insights on the Talmud known as Chiddushi HaGRaCh Al Shas. This book is known as "Reb Chaim's stencils" and contains analytical insights into Talmudical topics.

He married the daughter of Rabbi Refael Shapiro and had two famous sons, Rabbi Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik (also known as Rabbi Velvel Soloveitchik) who subsequently moved to Israel and Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik who moved to the United Statesand subsequently served as a Rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva Yitzchak Elchonon (YU/RIETS) in New York and who was in turn succeeded by his own son Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903–1993). Rabbi Velvel's son, Rabbi Meshulam Dovid Soloveitchik, heads a renowned yeshiva in Jerusalem; two of his other sons, Meir and Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, also led prominent yeshivas.

He had seven main students; his sons Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik and Rabbi Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, Rabbi Baruch Ber Lebowitz, Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman, Rabbi Shlomo Polachek, and Rabbi Shimon Shkop.

| [hide]

Brisker family tree

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment