| Haakon VII | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

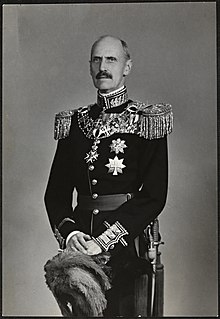

King Haakon in 1946

| |||||

| King of Norway | |||||

| Reign | 18 November 1905 − 21 September 1957 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 June 1906 | ||||

| Predecessor | Oscar II | ||||

| Successor | Olav V | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Born | 3 August 1872 Charlottenlund Palace, Copenhagen, Denmark | ||||

| Died | 21 September 1957(aged 85) Royal Palace, Oslo, Norway | ||||

| Burial | 1 October 1957 Akershus Castle, Oslo, Norway | ||||

| Spouse | Maud of Wales (m. 1896;d. 1938) | ||||

| Issue | Olav V of Norway | ||||

| |||||

| House | Glücksburg | ||||

| Father | Frederick VIII of Denmark | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Sweden | ||||

Rebuilding the nation

The Royal Family received a warm welcome on its return to Norway after the liberation on 7 June 1945. In late summer 1945 the King embarked on a tour of the country to see for himself the destruction wrought by the war, as well as the ongoing efforts to rebuild. He completed the second half of the tour the following summer.

Through a nationwide collection effort the Norwegian people raised the funds necessary to present King Haakon with a royal yacht on the occasion of his 75th birthday. The British motor yacht Philante was purchased, and the King was given a model of the vessel on his 75th birthday in 1947. The yacht was undergoing refurbishment, and was to be ready the following summer. King Haakon greatly appreciated this gift from the people, and re-christened the vessel the Norge. In the years that followed, he travelled extensively on the Norge. In summer 1955 he paid a visit to Møre and Romsdal County in Western Norway. It was to be his final voyage.

Funeral

King Haakon VII died at the Palace in Oslo on 21 September 1957, and was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Akershus Castle. Crowds of mourners lined the roads as the funeral cortège passed by.

http://www.royalcourt.no/artikkel.html?tid=28678&sek=28571

Resistance during World War II[edit]

The German invasion[edit]

Norway was invaded by the naval and air forces of Nazi Germany during the early hours of 9 April 1940. The German naval detachment sent to capture Oslo was opposed by Oscarsborg Fortress. The fortress fired at the invaders, sinking the heavy cruiser Blücher and damaging the heavy cruiser Lützow, with heavy German losses that included many of the armed forces, Gestapo agents, and administrative personnel who were to have occupied the Norwegian capital. This led to the withdrawal of the rest of the German flotilla, preventing the invaders from occupying Oslo at dawn as had been planned. The German delay in occupying Oslo, along with swift action by the President of the Storting, C. J. Hambro, created the opportunity for the Norwegian Royal Family, the cabinet, and most of the 150 members of the Storting (parliament) to make a hasty departure from the capital by special train.

The Storting first convened at Hamar the same afternoon, but with the rapid advance of German troops, the group moved on to Elverum. The assembled Storting unanimously enacted a resolution, the so-called Elverum Authorization, granting the cabinet full powers to protect the country until such time as the Storting could meet again.

The next day, Curt Bräuer, the German Minister to Norway, demanded a meeting with Haakon. The German diplomat called on Haakon to accept Adolf Hitler's demands to end all resistance and appoint Vidkun Quisling as prime minister. Quisling, the leader of Norway's fascist party, the Nasjonal Samling, had declared himself prime minister hours earlier in Oslo as head of what would be a German puppet government; had Haakon formally appointed him, it would have effectively given legal sanction to the invasion. Bräuer suggested that Haakon follow the example of the Danish government and his brother, Christian X, which had surrendered almost immediately after the previous day's invasion, and threatened Norway with harsh reprisals if it did not surrender. Haakon told Bräuer that he could not make the decision himself, but only on the advice of the Government. While Haakon would have been well within his rights to make such a decision on his own authority (since declaring war and peace are part of the royal prerogative), even at this critical hour he refused to abandon the convention that he acted on the Government's advice.

In an emotional meeting in Nybergsund, the King reported the German ultimatum to his cabinet. While Haakon could not make the decision himself, he knew he could use his moral authority to influence it. Accordingly, Haakon told the cabinet:

Haakon went on to say that he could not appoint Quisling as Prime Minister because he knew neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him. However, if the cabinet felt otherwise, the King said he would abdicate so as not to stand in the way of the Government's decision.

Nils Hjelmtveit, Minister of Church and Education, later wrote:

Inspired by Haakon's stand, the Government unanimously advised him not to appoint any government headed by Quisling. Within hours, it telephoned its refusal to Bräuer. That night, NRK broadcast the government's rejection of the German demands to the Norwegian people. In that same broadcast, the Government announced that it would resist the German invasion as long as possible, and expressed their confidence that Norwegians would lend their support to the cause

Resistance during World War II[edit]

The German invasion[edit]

Norway was invaded by the naval and air forces of Nazi Germany during the early hours of 9 April 1940. The German naval detachment sent to capture Oslo was opposed by Oscarsborg Fortress. The fortress fired at the invaders, sinking the heavy cruiser Blücher and damaging the heavy cruiser Lützow, with heavy German losses that included many of the armed forces, Gestapo agents, and administrative personnel who were to have occupied the Norwegian capital. This led to the withdrawal of the rest of the German flotilla, preventing the invaders from occupying Oslo at dawn as had been planned. The German delay in occupying Oslo, along with swift action by the President of the Storting, C. J. Hambro, created the opportunity for the Norwegian Royal Family, the cabinet, and most of the 150 members of the Storting (parliament) to make a hasty departure from the capital by special train.

The Storting first convened at Hamar the same afternoon, but with the rapid advance of German troops, the group moved on to Elverum. The assembled Storting unanimously enacted a resolution, the so-called Elverum Authorization, granting the cabinet full powers to protect the country until such time as the Storting could meet again.German diplomat called on Haakon to accept Adolf Hitler's demands to end all resistance and appoint Vidkun Quisling as prime minister.

The next day, Curt Bräuer, the German Minister to Norway, demanded a meeting with Haakon. The Quisling, the leader of Norway's fascist party, the Nasjonal Samling, had declared himself prime minister hours earlier in Oslo as head of what would be a German puppet government; had Haakon formally appointed him, it would have effectively given legal sanction to the invasion. Bräuer suggested that Haakon follow the example of the Danish government and his brother, Christian X, which had surrendered almost immediately after the previous day's invasion, and threatened Norway with harsh reprisals if it did not surrender. Haakon told Bräuer that he could not make the decision himself, but only on the advice of the Government. While Haakon would have been well within his rights to make such a decision on his own authority (since declaring war and peace are part of the royal prerogative), even at this critical hour he refused to abandon the convention that he acted on the Government's advice.

In an emotional meeting in Nybergsund, the King reported the German ultimatum to his cabinet. While Haakon could not make the decision himself, he knew he could use his moral authority to influence it. Accordingly, Haakon told the cabinet:

Haakon went on to say that he could not appoint Quisling as Prime Minister because he knew neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him. However, if the cabinet felt otherwise, the King said he would abdicate so as not to stand in the way of the Government's decision.

Nils Hjelmtveit, Minister of Church and Education, later wrote:

- Haarr, Geirr H. (2009). The German Invasion of Norway. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-032-1.[p

Inspired by Haakon's stand, the Government unanimously advised him not to appoint any government headed by Quisling. Within hours, it telephoned its refusal to Bräuer. That night, NRK broadcast the government's rejection of the German demands to the Norwegian people. In that same broadcast, the Government announced that it would resist the German invasion as long as possible, and expressed their confidence that Norwegians would lend their support to the cause

Government in exile[edit]

The following morning, 11 April 1940, in an attempt to wipe out Norway's unyielding king and government, Luftwaffe bombers attacked Nybergsund, destroying the small town where the Government was staying. Neutral Sweden was only 16 miles away, but the Swedish government decided it would "detain and incarcerate" King Haakon if he crossed their border (which Haakon never forgave).[9] The Norwegian king and his ministers took refuge in the snow-covered woods and escaped harm, continuing farther north through the mountains toward Molde on Norway's west coast. As the British forces in the area lost ground under Luftwaffe bombardment, the King and his party were taken aboard the British cruiser HMS Glasgow at Molde and conveyed a further 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north to Tromsø, where a provisional capital was established on 1 May. Haakon and Crown Prince Olav took up residence in a forest cabin in Målselvdalen valley in inner Troms County, where they would stay until evacuation to the United Kingdom. While residing in Tromsø, the two were protected by local rifle association members armed with the ubiquitous Krag-Jørgensen rifle.[citation needed]

The Allies had a fairly secure hold over northern Norway until late May. The situation was dramatically altered, however, by their deteriorating situation in the Battle of France. With the Germans rapidly overrunning France, the Allied high command decided that the forces in northern Norway should be withdrawn. The Royal Family and Norwegian Government were evacuated from Tromsø on 7 June aboard HMS Devonshire with a total of 461 passengers. This evacuation became extremely costly for the Royal Navy when the German warships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau attacked and sank the nearby aircraft carrier HMS Glorious with its escorting destroyers HMS Acasta and HMS Ardent. Devonshire did not rebroadcast the enemy sighting report made by Glorious as she could not disclose her position by breaking radio silence. No other British ship received the sighting report, and 1,519 British officers and men and three warships were lost. Devonshire arrived safely in London and King Haakon and his Cabinet set up a Norwegian government in exile in the British capital.

Initially, King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav were guests at Buckingham Palace, but at the start of the London Blitz in September 1940, they moved to Bowdown House in Berkshire. The construction of the adjacent RAF Greenham Commonairfield in March 1942 prompted another move to Foliejon Park in Winkfield, near Windsor, in Berkshire, where they remained until the liberation of Norway.[10] The King's official residence was the Norwegian Legation at 10 Palace Green, Kensington, which became the seat of the Norwegian government in exile. Here Haakon attended weekly Cabinet meetings and worked on the speeches which were regularly broadcast by radio to Norway by the BBC World Service. These broadcasts helped to cement Haakon's position as an important national symbol to the Norwegian resistance.[11] Many broadcasts were made from Saint Olav's Norwegian Church in Rotherhithe, where the Royal Family were regular worshippers.[12]

Meanwhile, Hitler had appointed Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar for Norway. On Hitler's orders, Terboven attempted to coerce the Storting to depose the King; the Storting declined, citing constitutional principles. A subsequent ultimatum was made by the Germans, threatening to intern all Norwegians of military age in German concentration camps.[13] With this threat looming, the Storting's representatives in Oslo wrote to their monarch on 27 June, asking him to abdicate. The King declined, politely replying that the Storting was acting under duress. The King gave his answer on 3 July, and proclaimed it on BBC radio on 8 July.[14]

After one further German attempt in September to force the Storting to depose Haakon failed, Terboven finally decreed that the Royal Family had "forfeited their right to return" and dissolved the democratic political parties.[15]

During Norway's five years under German control, many Norwegians surreptitiously wore clothing or jewellery made from coins bearing Haakon's "H7" monogram as symbols of resistance to the German occupation and of solidarity with their exiled King and Government, just as many people in Denmark wore his brother's monogram on a pin. The King's monogram was also painted and otherwise reproduced on various surfaces as a show of resistance to the occupation.[16]

After the end of the war, Haakon and the Norwegian Royal Family returned to Norway aboard the cruiser HMS Norfolk, arriving with the First Cruiser Squadron to cheering crowds in Oslo on 7 June 1945,[17] exactly five years after they had been evacuated from Tromsø.[18]

Death and legacy[edit]

King Haakon VII passed away at the Royal Palace in Oslo on the 21 September 1957. He was 85 years old. At Haakon's death, Olav succeeded him as Olav V. Haakon was buried on 1 October 1957. He and Maud rest in the white sarcophagus in the Royal Mausoleum at Akershus Fortress. He was the last surviving son of King Frederick VIII of Denmark.

Today, King Haakon VII is regarded by many as one of the greatest Norwegian leaders of the pre-war period, managing to hold his young and fragile country together in unstable political conditions. He was ranked highly in the Norwegian of the Centurypoll in 2005.

http://www.royalcourt.no/artikkel.html?tid=28678&sek=28571

World War II

German troops invaded Norway on 9 April 1940, planning to capture the King and the Government to force the country to capitulate. However, the Royal Family, the Government and most members of the Storting were able to flee before the occupying forces reached Oslo.

Convened at Elverum in Eastern Norway, the Storting gave the King and the Government full authority to rule the country for the duration of the war. The Germans demanded that the King appoint a government headed by Nazi sympathiser Vidkun Quisling. The King stated that he would not attempt to influence the decision of the Government in this matter, but that he would abdicate if they chose to comply with the German ultimatum. Upon learning of the King’s refusal, German forces repeatedly bombed the village of Nybergsund where he was staying. Fortunately, he and the Crown Prince managed to escape to safety.

On 7 June 1940 the King, the Crown Prince and the Government travelled from Tromsø to England, establishing a government in exile in London to lead the resistance effort. King Haakon became the foremost symbol of the Norwegian people’s will to fight for a free and independent Norway, and his radio broadcasts from London served as a source of inspiration for young and old alike.

No comments:

Post a Comment