Christic Institute

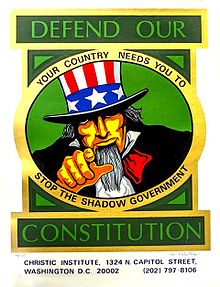

Christic Institute poster. Photo courtesy of their successor organization, the Romero Institute.

| |

| Founder(s) | Daniel Sheehan, Sara Nelson, Father Bill Davis |

|---|---|

| Established | 1980 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Website | Christic Archives at the Romero Institute |

| Dissolved | 1991 |

| In 1998, Christic was succeeded by the Romero Institute, with Daniel Sheehan and Sara Nelson continuing as leaders. | |

The Christic Institute was a public interest law firm founded in 1980 by Daniel Sheehan, his wife Sara Nelson, and their partner, William J. Davis, a Jesuit priest, after the successful conclusion of their work on the Silkwood case. Based on the ecumenical teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and on the lessons they learned from their experience in the Silkwood fight, the Christic Institute combined investigation, litigation, education and organizing into a unique model for social reform in the United States. In 1992 the firm lost its non-profit status after having a federal case dismissed by the court in 1988 and being penalized for filing a "frivolous lawsuit". The IRS said that the Christic Institute had acted for political reasons. The case was related to journalists injured in relation to the Iran-Contra Affair. The group was succeeded by a new firm, the Romero Institute.

Christic notably represented victims of the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island; they prosecuted KKK and American Nazi Party members for killing communist workers party demonstrators in the 1979 Greensboro Massacre, as well as police and federal agents whom they said had known about potential violence and had not adequately protected the victims; and they defended Catholic workers providing sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees (American Sanctuary Movement). Its headquarters were in Washington, D.C., with offices in several other major United States cities. The Institute received funding from a nationwide network of grassroots donors, as well as organizations like the New World Foundation.

Writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, Chip Berlet described the Christic Institute as "something of a rarity among advocacy groups: starting out on the left of the political spectrum, over the years it was drawn into the conspiracy theories woven by the radical right."[1] Christic Institute

Christic Institute poster. Photo courtesy of their successor organization, the Romero Institute.

| |

| Founder(s) | Daniel Sheehan, Sara Nelson, Father Bill Davis |

|---|---|

| Established | 1980 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Website | Christic Archives at the Romero Institute |

| Dissolved | 1991 |

| In 1998, Christic was succeeded by the Romero Institute, with Daniel Sheehan and Sara Nelson continuing as leaders. | |

The Christic Institute was a public interest law firm founded in 1980 by Daniel Sheehan, his wife Sara Nelson, and their partner, William J. Davis, a Jesuit priest, after the successful conclusion of their work on the Silkwood case. Based on the ecumenical teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and on the lessons they learned from their experience in the Silkwood fight, the Christic Institute combined investigation, litigation, education and organizing into a unique model for social reform in the United States. In 1992 the firm lost its non-profit status after having a federal case dismissed by the court in 1988 and being penalized for filing a "frivolous lawsuit". The IRS said that the Christic Institute had acted for political reasons. The case was related to journalists injured in relation to the Iran-Contra Affair. The group was succeeded by a new firm, the Romero Institute.

Christic notably represented victims of the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island; they prosecuted KKK and American Nazi Party members for killing communist workers party demonstrators in the 1979 Greensboro Massacre, as well as police and federal agents whom they said had known about potential violence and had not adequately protected the victims; and they defended Catholic workers providing sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees (American Sanctuary Movement). Its headquarters were in Washington, D.C., with offices in several other major United States cities. The Institute received funding from a nationwide network of grassroots donors, as well as organizations like the New World Foundation.

Writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, Chip Berlet described the Christic Institute as "something of a rarity among advocacy groups: starting out on the left of the political spectrum, over the years it was drawn into the conspiracy theories woven by the radical right."[1]

Contents

Three Mile Island, Greensboro Massacre, American Sanctuary Movement[edit]

In 1979, Daniel Sheehan, Sara Nelson and many of the allies and architects of the Silkwood case gathered in Washington, D.C. to found The Christic Institute. Over the next 12 years, as General Counsel for the Institute, Sheehan helped prosecute some of the most celebrated public interest cases of the time. Christic represented victims of the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island.

They conducted a civil suit, seeking damages from KKK and American Nazi Party (ANP) members for the murder of five civil rights demonstrators in the Greensboro Massacre. In addition, they charged the city, certain police and four Federal agents with having known of the potential for violence and failing to protect the protesters. The jury awarded damages to the plaintiffs against the city, the police department, and the KKK and ANP.

The Institute defended Catholic workers providing sanctuary to Salvadoran refugees in the American Sanctuary Movement.

The graphic novel Brought to Light, by writers Alan Moore and Joyce Brabner, used material from lawsuits filed by the Christic Institute.

Avirgan v. Hull[edit]

In 1986, the Christic Institute filed a $24 million civil suit on behalf of journalists Tony Avirgan and Martha Honey stating that various individuals were part of a conspiracy responsible for the La Penca bombing that injured Avirgan.[2][3] The suit charged the defendants of illegally participating in assassinations, as well as arms and drug trafficking.[2] Among the 30 defendants named were Iran–Contra figures John K. Singlaub, Richard V. Secord, Albert Hakim, and Robert W. Owen; Central Intelligence Agency officials Thomas Clines and Theodore Shackley; Contra leader Adolfo Calero; Medellin cartel leaders Pablo Escobar Gaviria and Jorge Ochoa Vasquez; Costa Rican rancher John Hull; and former mercenary Sam N. Hall.[2][3][4]

On June 23, 1988, United States federal judge James Lawrence King of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida dismissed the case stating: "The plaintiffs have made no showing of existence of genuine issues of material fact with respect to either the bombing at La Penca, the threats made to their news sources or threats made to themselves."[2] According to The New York Times, the case was dismissed by King at least in part due to "the fact that the vast majority of the 79 witnesses Mr. Sheehan cites as authorities were either dead, unwilling to testify, fountains of contradictory information or at best one person removed from the facts they were describing."[5] On February 3, 1989, King ordered the Christic Institute to pay $955,000 in attorneys fees and $79,500 in court costs.[3] The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the ruling, and the Supreme Court of the United States let the judgment stand by refusing to hear an additional appeal.[4][6] The IRS stripped the Institute of its 501(c)(3) nonprofit status after claiming the suit was politically motivated.[7][page needed][8] The fine was levied in accordance with “Rule 11” of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which says that lawyers can be penalized for frivolous lawsuits.[9]

In the wake of the dismissal, Christic attorneys and Honey and Avirgan traded accusations over who was to blame for the failure of the case. Avirgan complained that Sheehan had handled matters poorly by chasing unsubstantiated "wild allegations" and conspiracy theories, rather than paying attention to core factual issues.[10]

The Christic Institute was succeeded by the Romero Institute.

External links

The La Penca bombing was a bomb attack on May 30, 1984, in the guerrilla outpost of La Penca in Nicaragua, near the Costa Rican border. It occurred during a press conference being conducted by Edén Pastora, a leader of the Contras, who is presumed to have been the target.[1] Seven people, including three journalists, were killed in the attack.

Attack

A press conference had been arranged in the guerrilla outpost of La Penca by Pastora, a former Sandinista who had switched allegiance to the Contras. The press conference took place in an enclosed hut on stilts, near the northern bank of the San Juan River, which separates Costa Rica from Nicaragua. The press conference had been convened by Contra officials in the Costa Rican capital of San José, and the journalists arrived to La Penca in the middle of the night after traveling all day over land and by canoe from San José. Because of the late hour, Pastora initially asked for the press conference to start in the morning, but as the reporters began peppering the guerrilla leader with questions, an impromptu press conference began, and the reporters and television news crews gathered with Pastora around a chest-high table situated in the main room of the hut.

The bomb is believed to have been hidden in an aluminum camera case and planted by an individual carrying a stolen Danish passport. According to witnesses, the bomber used the name "Per Anker Hansen" and claimed to be a Danish photographer.[2]

Afterwards, bombing survivors commented that they found it odd that "Hansen" had so zealouly guarded his "camera equipment" by wrapping the unwieldy aluminum box in plastic. "Hansen" is believed to have deposited the camera case containing the bomb under the table. News footage later showed the suspected bomber gesturing to his camera, as if to indicate an equipment malfunction as a pretext to leave the room. The bomber is suspected to have detonated the bomb remotely using a walky-talky signal as a detonator. Seconds after "Hansen" left the room, an explosion ripped through the hut, which left the injured and dying crying out in pain and calling for help in sudden darkness.

Those killed in the bombing were an American journalist, Linda Frazier; a Costa Rican cameraman, Jorge Quiros; his assistant, Evelio Sequeira; and four rebels.

Also, Pastora was seriously injured in both legs. About a dozen other people were seriously injured.[1]

Investigation

The bombing led to an investigation by Tony Avirgan, an American journalist injured in the bombing, and his wife, Martha Honey. Both concluded that the CIA was responsible.[3] In 1986, the Christic Institute filed a $24 million lawsuit on their behalf against several individuals all associated with Oliver North, including Rob Owen, John Hull, Richard Secord, Albert Hakim, and Thomas Clines.[3] However, the case was thrown out in June 1988, and the Christic Institute was ordered to pay approximately $1 million in costs to the defendants.[4]

In 1990, the government of Costa Rica accused the CIA of orchestrating the bombing by two intermediaries. Charges of murder were laid against Felipe Vidal, a Cuban-American, and John Hull, an American farmer who lived in Costa Rica at the time[2] and had been previously named in the Christic Institute lawsuit.[4]

In 1993, Miami Herald reporter Juan Tamayo and Doug Vaughn, a freelance journalist working for the Christic Institute, established the identity of the alleged bomber to be an Argentine lefitist named Vital Roberto Gaguine, who had worked with the Sandinista militia in the early 1980s. Tamayo got a tip from a former member of Argentina's People's Revolutionary Army, who defected and was living in Europe and recognized news photographs of "Per Anker Hansen" to be a former member of the leftist group. Around the same time, Vaughn unearthed a photo of "Hansen" along with a right thumbprint from Panamanian government files. Argentine journalists obtained fingerprints of Gaguine from Argentine authorities and Vaughn and Tamayo took the two sets of prints to a fingerprint expert in Miami, who found a perfect match. Vaughn showed newsphotos of Gaguine to the alleged bomber's brother and father who confirmed the identification. According to Argentine journalists cited by Tamayo, Gaguine was among a group of guerrillas who died in an attack on the Argentine military base of La Tablada in 1989.[5] However, in 2008, Costa Rica's chief prosecutor who saw Gaguine's file in Buenos Aires said that Argentine authorities never made a positive identification of Gaguine's body and that the case remains open.[6] The association between the perpetrator and the FSLN led Tamayo to conclude that the Sandinistas were solely responsible.[2] In an article in The Nation, Tony Avirgan concurred.[7]

In 2009, Swedish journalist and La Penca survivor Peter Torbiörnsson broke 25 years of silence to reveal that he knew in advance of "Hansen"'s connection to the Sandinistas. He reported that he was introduced to the bomber in Managua by the Chief of Sandinista intelligence, a Cuban named Renan Montero. Torbiörnsson took "Hansen" under his wing and provided journalistic cover as the two traveled throughout northern Costa Rica in search of Pastora. The Swede, who admitted sympathy with the Sandinista cause, said that he suspected his travel companion was a spy but that he had no idea he was an assassin. Even as journalists and news organizations spent years trying to crack the La Penca mystery, Torbiörnsson kept silent about his knowledge of the bomber's Sandinista connection. However, tormented by the idea that he had been used as an unwitting accomplice to a terrorist attack, Torbiörnsson finally broke his silence by traveling to Managua in January 2009, to present an accusation before Nicaraguan police authorities pointing to Montero, former Sandinista Minister of Interior Comandante Tomás Borge and Lenín Cerna, ex-chief of state security as intellectual authors of the attack.[8]

In 2011, Torbiörnsson released a documentary film, Last Chapter, Goodbye Nicaragua, which premiered in the DocsBarcelona International Film Festival and renewed his accusation that Sandinista leaders Borge, Cerna, and Montero ordered the bombing. Torbiörnsson also claimed that Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega admitted to him five years after the attack that the bombing had been orchestrated by his government but that Ortega later chose to cover it up and buy Pastora's silence and co-operation in exchange for a position within the second Sandinista administration.[9]

References - Gruson, Lindsay (1990-03-01). "Turnover in Nicaragua; Costa Rica Is Asking U.S. to Extradite Rancher Tied to '84 Bombing That Killed 4". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- "Costa Rica Reopens Inquiry in 1984 Bombing". New York Times. 1993-08-08. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- "La Penca and beyond". The Progressive. 1996-06-01. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- "CHRISTIC INSTITUTE ORDERED TO PAY $1M". Boston Globe. Associated Press. 1989-02-04. Archived from the original on 2013-01-29. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- Tamayo, Juan (1993-08-01). "'84 Bomb Mystery Unravels Sandinista Tied to Jungle Deaths". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- McPhaul, John (2008-08-01). "Costa Rica's chief prosecutor snubs Swede's account of bombing". The Tico Times. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- "Unmasking the la Penca Bomber," The Nation, 1993-09-06.

- Rogers, Tim (2009-01-30). "Bombing survivor seeks truth, closure". The Nica Times. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- Sanchís, Ima (2011-02-11). "El amor y la verdad van cogidos de la mano". La Vanguardia. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

La Penca: Thirty years later (Tico Times article on the 30th anniversary of the bombing)

No comments:

Post a Comment