Lancelot Andrewes

This was the loadstar of the Magi, and

what were they? Gentiles. So are we. But it if must be ours, then we are to go

with them; vade, et fac similiter, Ôgo, and do thou likewise.Õ It

is Stella gentium, but idem agentium Ôthe Gentiles' star,Õ

but Ôsuch Gentiles as overtake these and keep company with them.Õ In their

dicentes, Ôconfessing their faith freely;Õ in their vidimus,

Ôgrounding it throughly;Õ in their venimus, Ôhasting to come to

Him speedily;Õ in their ubi est Ôenquiring Him out diligently;Õ

and in their adorare um, Ôworshipping Him devoutly.Õ Per omnia

doing as these did; worshipping and thus worshipping, celebrating and thus

celebrating the feast of His birth

| The Right Reverend and Right Honourable Lancelot Andrewes | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Winchester | |

"Bishop Andrews", c. 1660

| |

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Winchester |

| In office | 1619–1626 |

| Predecessor | James Montague |

| Successor | Richard Neile |

| Other posts | Dean of the Chapel Royal (1618–1626) Bishop of Ely (1609–1619) Lord Almoner (1605–1619) Bishop of Chichester (1605–1609) Dean of Westminster (1601–1605) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | c. 1579 (deacon); 1580 (priest) |

| Consecration | 1605 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1555 All Hallows-by-the-Tower, City of London, England |

| Died | 25 September 1626 (aged 70–72) Southwark, Surrey, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Residence | Winchester House, Southwark (at death) |

| Parents | Thomas Andrewes (father) |

| Occupation | Preacher; translator |

| Alma mater | Pembroke Hall, Cambridge |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

|---|---|

| Feast | 25 September (Church of England) 26 September (ECUSA) |

Contents

[hide]Early life, education and ordination[edit]

Andrewes was born in 1555 near All Hallows, Barking, by the Tower of London, of an ancient Suffolk family later domiciled at Chichester Hall, at Rawreth in Essex; his father, Thomas, was master of Trinity House. Andrewes attended the Cooper's free school, in Ratcliff, in the parish of Stepney and then the Merchant Taylors' School under Richard Mulcaster. In 1571 he entered Pembroke Hall, Cambridge and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree, proceeding to a Master of Arts degree in 1578.[1] His academic reputation spread so quickly that on the foundation in 1571 of Jesus College, Oxford he was named in the charter as one of the founding scholars "without his privity" (Isaacson, 1650); his connection with the college seems to have been purely notional, however.[2] In 1576 he was elected fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge; on 11 June 1580 he was ordained a priest by William Chaderton, Bishop of Chester[3] and in 1581 was incorporated Master of Arts (MA) at Oxford. As catechist at his college he read lectures on the Decalogue (published in 1630), which aroused great interest.Once a year he would spend a month with his parents, and during this vacation, he would find a master from whom he would learn a language of which he had no previous knowledge. In this way, after a few years, he acquired most of the modern languages of Europe.[4]

Andrewes was the elder brother of the scholar and cleric Roger Andrewes, who also served as a translator for the King James Version of the Bible.

During Elizabeth's reign[edit]

In 1588, following a period as chaplain to Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, Lord President of the Council in the North, he became vicar of St Giles, Cripplegate in the City of London, where he delivered striking sermons on the temptation in the wilderness and the Lord's Prayer. In a great sermon (during Easter week) on 10 April 1588, he stoutly vindicated the Reformed character of the Church of England against the claims of Roman Catholicism and adduced John Calvin as a new writer, with lavish praise and affection.Through the influence of Francis Walsingham, Andrewes was appointed prebendary of St Pancras in St Paul's, London, in 1589, and subsequently became Master of his own college of Pembroke, as well as a chaplain of Archbishop John Whitgift. From 1589 to 1609 he was prebendary of Southwell. On 4 March 1590, as a chaplain of Elizabeth I, he preached before her an outspoken sermon and, in October that year, gave his introductory lecture at St Paul's, undertaking to comment on the first four chapters of the Book of Genesis. These were later compiled as The Orphan Lectures (1657).

Andrewes liked to move among the people, yet found time to join a society of antiquaries, of which Walter Raleigh, Sir Philip Sidney, Burleigh, Arundel, the Herberts, Saville, John Stow and William Camden were members. Queen Elizabeth had not advanced him further on account of his opposition to the alienation of ecclesiastical revenues. In 1598 he declined the bishoprics of Ely and Salisbury, because of the conditions attached. On 23 November 1600, he preached at Whitehall a controversial sermon on justification. In July 1601 he was appointed dean of Westminster and gave much attention to the school there.

http://anglicanhistory.org/lact/andrewes/v1/ Sermon Nativity

http://anglicanhistory.org/lact/andrewes/v1/sermon15.html

- Project Canterbury

Library of Anglo-Catholic Theology - Lancelot Andrewes Works, Sermons, Volume One

- SERMONS OF THE NATIVITY.

PREACHED UPON CHRISTMAS-DAY, 1622.

Preached before King James, at Whitehall, on Wednesday, the Twenty-fifth of December, A.D. MDCXXII. - Transcribed by Dr Marianne Dorman

AD 2001

St. Matthew ii:1-2Behold there came wise men from the East to Jerusalem, Saying, Where is He That is born King of the Jews? for we have seen His star in the East, and are come to worship Him.Ecce magi ab Oriente venerunt Jerosolymam, Dicentes, Ubi est Qui natus est Rex Judaeorum? Vidimus enim stellam Ejus in Oriente, et venimus adorare Eum.There be in these two verses two principal points, as was observed when time was; 1. The persons that arrived at Jerusalem, 2. and their errand. The persons in the former verse, whereof hath been treated heretofore. Their errand in the latter, whereof we are now to deal.Their errand we may best learn from themselves out of their dicentes &c. Which, in a word, is to worship Him. Their errand our errand, and the errand of this day.This text may seem to come a little too soon, before the time; and should have stayed till the day it was spoken on, rather than on this day. But if you mark them well, there are in the verse four words that be verba diei hujus, Ôproper and peculiar to this very day.Õ 1. For first, natus est is most proper to this day of all days, the day of His Nativity. 2. Secondly, vidimus stellam; for on this day it was first seen, appeared first. 3. Thirdly, venimus; for this day they set [249/250] forth, began their journey. 4. And last, adorare Eum; for Ôwhen He brought His only-begotten Son into the world, He gave in charge, Let all Angels of God worship Him.Õ And when the Angels to do it, no time more proper for us to do it as then. So these four appropriate it to this day, and none but this.The main heads of their errands are 1. Vidimus stellam, the occasion; 2. and Venimus adorare, the end of their coming. But for the better conceiving it I will take another course, to set forth, these points to be handled.Their faith first: faithÑin that they never ask ÔWhether He be,Õ but ÔWhere He is born;Õ for that born He is that they stedfastly believe.Then Ôthe work or serviceÕ of this faith, as St. Paul calleth it, Ôthe touch or trial,Õ dokÉmion, as St. Peter; the ostende mihi, as St. James; of this their faith in these five. 1. Their confessing of it in venerunt dicentes. Venerunt, they were no sooner come, but they tell it out; confess Him and His birth to be the cause of their coming. 2. Secondly, as confess their faith, so the ground of their faith; vidimus enim, for they had ÔseenÕ His star; and His star being risen, by it they knew He must be risen too. 3. Thirdly, as St. Paul calls them in Abraham's, vetigia fidei, Ôthe steps of their faith,Õ in venimus, Ôtheir comingÕÑcoming such a journey, at such a time, with such speed. 4. Fourthly, when they were come, their diligent enquiring Him out by ubi est.? for here is the place of it, asking after Him to find where He was. 5. And last, when they had found Him, the end of their seeing, coming, seeking; and all for no other end but to worship Him. Here they say it, at the 11th verse they do it in these two acts; 1. procidentes, their Ôfalling down,Õ 2. and obtulerunt, their ÔofferingÕ to Him. Worship with Him with their bodies, worship Him with their goods; their worship and ours the true worship of Christ.The text is a star, and we may make all run on a star, that so the text and day may be suitable, and Heaven and earth hold a correspondence. St. Peter calls faith Ôthe day-star rising in our hearts,Õ which sorts well with the star in the text rising in the sky, That in the sky manifesting itself from above to them; this in their hearts manifesting itself from [250/251] below to Him, to Christ. Manifesting itself by these five. 1. by ore fit confessio, Ôthe confessing of it;Õ 2. by fides est substantia, Ôthe ground of it;Õ 3. by vestigia fidei, Ôthe steps of itÕÕ in their painful coming; 4. by their ubi est? Ôcareful enquiring;Õ 5. and last, by adorare Eum, Ôtheir devout worshipping.Õ These five, as so many beams of faith, the day-star risen in their hearts. To take notice of them. For every one of them is of the nature of a condition, so as if we fail in them. non lucet nobis stella h¾c, Ôwe have no part in the light, or conduct of this star.Õ Neither in stellam, Ôthe star itself,Õ nor in Ejus, Ôin Him Whose the star is;' that is, not in Christ neither.We have now got us a star on earth for that in Heaven. The first in the firmament; that appeared unto them, and in them to usÑa figure of St. Paul's :Epef£nh c£rijt, Ôthe grace of God appearing, and bringing salvation to all men,Õ Jews and Gentiles alike. The second here on earth is St.Peter's, Lucifer in cordibus; and this appeared in them, and so must in us. Appeared 1. in their eyesÑvidimus; 2 in their feetÑvenimus; 3. in their lipsÑdicentes ubi est; 4. in their kneesÑprocidentes, Ôfalling down;Õ 5. in their handsÑobtulerunt, Ôby offering.Õ These five every one a beam of this star. 3. The third in Christ Himself, St.John's star. ÔThe generation and root of David, the bright morning star, Christ.Õ And He, His double appearing. 1. One at this time now, when He appeared in great humility; and we see and come to him by faith. 2. The other, which we wait for, even Ôthe blessed hope, and appearing of the great God and our SaviourÕ in the majesty of His glory.These three: 1. The first that manifested Christ to them; 2. the second that manifested them to Christ; 3. The third Christ Himself, in Whom both these were as it were in conjunction. Christ Ôthe bright morning starÕ of that day which will have no night; the beatifica visio of which day is the consummatum est of our hope and happiness for ever.Of these three stars the first is gone, the third yet to come, the second only present. We to look to that, and to [251/252] the five beams of it. That is it must do us all the good, and bring us to the third.St. Luke calleth faith the Ôdoor of faith.Õ At this door let us enter. Here is a coming, and Ôhe that cometh to God,Õ and so he that to Christ, Ôwe must believe, that Christ is;Õ so do these. They never ask an sit, but ubi sit? Not ÔwhetherÕ but Ôwhere He is born.Õ They that ask ubi Qui natus? take natus for granted, presuppose that born He is. Herein is faithÑfaith of Christ's being born, the third article of the Christian Creed.And what they believe they of Him? Out of their own words here; 1. first that natus, that ÔbornÕ He is and so Man He is,Ñ His human nature. 2. And as His nature, so His office in natus est Rex. They believe that too. 3. But Judaeorum may seem to be a bar; for then, what have they to do with Ôthe King of the Jews?Õ They be Gentiles, none of His lieges, no relation to Him at all; what do they seeking or worshipping Him? But weigh it well, and it is no bar. For this they seem to believe: He is so Rex Judaeorum, Ôthe King of the Jews,Õ as He is adorandus a Gentibus, Ôthe Gentiles to adore Him.Õ And though born in Jewry, yet Whose birth concerned them though Gentiles, though born far off in the Ômountains of the east.Õ They to have some benefit by Him and His birth, and for that to do Him worship, seeing officum fundatur in beneficio ever. 4. As thus born in earth, so a star He hath in Heaven of His ownÑstellam Ejusi, ÔHis star;Õ He the owner of it. Now we know the stars are the stars of Heaven, and He that Lord of them Lord of Heaven too; and so to be adored of them, of us, and all. St. John puts them together; Ôthe root and generation of David,Õ His earthly; and Ôthe bright morning star,Õ His Heavenly or Divine generation. H¾c fides Magorum, this is the mystery of their faith. In natus est, man; in stellam Ejus, God. In Rex, Ôa King,Õ though of the Jews, yet the god of Whose Kingdom should extend and stretch itself far and wide to Gentiles and all; and He of all to be adored. This for corde creditur, the day-star itself in their hearts. Now to the beams of this star.Next to corde creditur is ore fit confessio, Ôthe confessionÕ of this faith. It is in venerunt dicentes, they came with it in [252/253] their mouths. Venerunt, they were no sooner come, but they spake of it so freely, to so many, as it came to Herod's ear and troubled him not a little that any King of the Jews should be worshipped beside himself. So then their faith is no bosom-faith, kept to themselves without saying anything of it to anybody. No; credidi, propter quod lecutus sum, Ôthey believed, and therefore they spake.Õ The star in their hearts cast one beam out at their mouths. And though Herod who was but Rex factus could evil brook of Rex natus,Ñ must needs be offended at it, yet they were not afraid to say it. And though they came from the East, those parts to whom and their King the Jews had long time been captives and their underlings, they were not ashamed neither to tell, that One of the Jews' race they came to seek; and to seek Him to the end Ôto worship Him.Õ So neither afraid of Herod, nor ashamed of Christ; but professed their errand, and cared not who knew it. This for their confessing Him boldly.But faith is said by the Apostle to be, ¯pñstasij, and so there is a good Ôground;Õ and Ïlegxoj, and so hath a good ÔreasonÕ for it. This puts a difference between fidelis and credulus, or as Solomon terms him fatus, qui credit omni verbo; between faith and lightness of belief. Faith hath ever as ground; vidimus enim,Ñan enim, a reason for it, and is ready to render it. How came you to believe? Audivimus enim, Ôfor we have heard and Angel,Õ say the shepherds. Vidimus enim, Ôfor we have seen a starÕ say the Magi, and this is a well-grounded faith. We came not of our own heads, we came not before we saw some reason for itÑsaw that which set us on coming; Vidimus enim stellam Ejus.Vidimud stellamÑwe can well conceive that; any that will but look up, may see a star. But how could they see the Ejus of it, that it was His? Either that it belonged to any, or that He it was it belonged to. This passeth all perspective; no astronomy could shew them this. What by course of nature the star can produce, that they by course of nature the stars can produce, that they by course of art or observation may discover. But this birth was above nature. No trigon, triplicity, exaltation could bring it forth. They are but idle that set figures for it. The star should not have been [253/254] His, but He the star's, if it had gone that way. Some other light then, they saw this Ejus by.Now with us in Divinity there be but two in all; 1. Vespertina, 2. Matutina lux. Vespertina, Ôthe owl- lightÕ of our reason or skill is too dim to see it by. No remedy then but it must be as Esay calls it, matutina lux, Ôthe morning-light,Õ the light of God's law must certify them of the Ejus of it. There, or not at all to be had whom this star did portend.And in the Law, there we find it in the twenty-fourth of Numbers. One of their own Prophets that came from whence they came, Ôfrom the mountains of the East,Õ was ravished in spirit, Ôfell in a trance, had his eyes opened,Õ and saw the Ejus if it many an hundred years before it rose. Saw orietur in Jacob, that there it should Ôrise,Õ which is as much as natus est here. Saw stella, that He should be Ôthe bright morningÑStar,Õ and so might well have a star to represent Him. Saw sceptrum in Israel, which is just as much as Rex Jud¾orum, that it should portend a King thereÑsuch a King as should not only Ôsmite the corners of Moab,Õ that is Balak their enemy for the present; but Ôshould reduce and bring under Him all the sons of Seth,Õ that is all the world; for all are now Seth's sons, Cain's were all drowned in the flood. Here now is the Ejus of it clear. A Prophet's eye might discern this; never a Chaldean of them all could take it with his astrolabe. Balaam's eyes were opened to see it, and he helped to open their eyes by leaving behind him this prophecy to direct them how to apply it, when it should arise to the right Ejus of it.But these had not the law. It is hard to say that the Chaldee paraphrase was extant long before this. They might have had it. Say, they had it not: if Moses were so careful to record this prophecy in his book, it may well be thought that some memory of this so memorable a prediction was left remaining among them of the East, his own country, where he was born and brought up. And some help they might have from Daniel too, who lived all his time in Chaldea and Persia, and prophesied among them of such a King, and set the just time of it.And this, as it is conceived, put the difference between [254/255] the East and the West. For I ask, was it vidimus in Oriente with them? Was it not vidimus in Occidente? In the West such a starÑit or the fellow of it was seen nigh about that time, or the Roman stories deceive us. Toward the end of Augustus' reign such a star was seen, and much scanning there was about it. Pliny saith it was generally holden, that star to be faustum sydus, Ôa lucky comet,Õ and portended good to the world, which few or no comets do. And Virgil, who then lived, would needs take upon him to set down the ejus of it.Ecce Dion¾i &c.Ñentitled C¾sar to it. And verily there is no man that can without admiration read his sixth Eclogue, of a birth that time expected, that should be the offspring of the gods, and that should take away their sins. Whereupon it hath gone for currentÑthe East and West, vidimus both.But by the light of their prophecy, the East they went straight to the right Ejus. And for want of this light the West wandered, and gave it a wrong ejus; as Virgil, applying it to little Salonine: and as evil hap was, while he was making his verses, the poor child died; and so his star shot, vanished, and came to nothing. Their vidimus never came to a venimus; they neither went, nor worshipped Him as these here did.But by this we see, when all is done, hither we must come for our morning light; to this book, to the word of prophecy. All our vidimus stellam is as good as nothing without it. The star is past and gone, long since. ÔHeaven and earth shall pass, but this word shall not pass.Õ Here on this, we to fix our eye and to ground our faith. Having this, though we neither hear Angel nor see star, we may by the grace of God do full well. For even they that have had both those, have been fain to resolve into this as their last, best, and chiefest point of all. Witness St. Peter: he, saith he, and they with him, Ôsaw Christ's glory, and heard the voice from Heaven in the Holy Mount.Õ What then? After both these audivimus and vidimus, both senses, he comes to this, habemus autem firmiorem, &c. ÔWe have a more sure word of prophecyÕ than both these; firmiorem, a more clear, than them both. And si h”c legimus Ñfor legimus is vidimus, Ôif here we read it written,Õ it is enough to ground our faith, and let the star go. [255/256]And yet, to end this point; both these, the star and the prophecy, they are but circumfusa luxÑwithout both. Besides these there must be a light within the eye; else, we know, for all them nothing will be seen. And that must come from Him, and the enlightening of His Spirit. Take this for a rule; no knowing of Ejus absque Eo, Ôof His without Him,Õ Whose it is. Neither of the star, without Him That inspired it. But this third coming too; He sending the light of His Spirit within into their minds, they then saw clearly, this the star, now the time, He the Child who this day was born. He That sent these two without, sent also this third within, and then it was vidimus indeed. The light of the star in their eyes, Ôthe word of prophecyÕ in their ears, the beam of His Spirit in their hearts; these three made up a full vidimus. And so much for vidimus stellam Ejus, the occasion of their coming.Now to venimus. their coming itself. And it follows well. For it is not a star only, but a load-star; and whither should stella Ejus ducere, but ad Eum? ÔWhither lead us, but to Him Whose the star is?Õ The star to the star's Master.All this while we have been at dicentes, ÔsayingÕ and seeing; now we shall come to facientes, see them do somewhat upon it. It is not saying nor seeing will serve St. James; he will call, and be still calling for ostende mihi, shew me thy faith by some work.Õ And well may he be allowed to call for it this day; it is the day of vidimus, appearing, being seen. You have seen His star, let Him now see your star another while. And so they do. Make your faith be seen; so it isÑ their faith in the steps of their faith. And so was Abraham's first by coming forth of his country; as these here do, and so Ôwalk in the steps of the faith of Abraham,Õ do his first work..It is not commended to stand Ôgazing up to heavenÕ too long; not on Christ Himself ascending, much less on His star. For they sat not still gazing on the star. Their vidimus begat venimus; their seeing made them come, come a great journey. Venimus is soon said, but a short word; but many a wide and weary step they made before they could come to say venimus; lo, here Ôwe are come;Õ come, and at [256/257] our journey's end. To look a little on it. In this their coming we consider, 1. First, the distance of the place they came from. It was not hard by as the shepherdsÑbut a step to Bethlehem over the fields; this was riding many a hundred miles, and cost them many a day's journey. 2. Secondly, we consider the way that they came, if it be pleasant, or plain and easy; for if it be, it is so much the better. 1. This was nothing pleasant, for through deserts, all the way waste and desolate. 2. Nor secondly, easy neither; for over the rocks and crags of both Arabias, specially Petr¾a, their journey lay. 3. Yet if safeÑbut it was not, but exceeding dangerous, as lying through the midst of the Ôblack tents of Kedar,Õ a nation of thieves and cut-throats; to pass over the hills of robbers, infamous then, and infamous to this day. No passing without great troop or convoy. 4. Last we consider the time of their coming, the season of the year. It was no summer progress. A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solsitio brumali, Ôthe very dead of winter.Õ Venimus, Ôwe are come,Õ if that be one, venimus, Ôwe are now come,Õ come at this time, that sure is another.And these difficulties they overcame, of a wearisome, irksome, troublesome, dangerous, unseasonable journey; and for all this they came. And came it cheerfully and quickly, as appeareth by the speed they made. It was but vidimus, venimus, with them; Ôthey saw,Õ and Ôthey came;Õ no sooner saw, but they set out presently. So as upon the first appearing of the star, as it might be last night, they knew it was Balaam's star; it called them away, they made ready straight to begin their journey this morning. A sign they were highly conceited of His birth, believed some great matter of it, that they took all these pains, made all this haste that they might be there to worship Him with all the possible speed they could. Sorry for nothing so much as that they could not be there soon enough, with the very first, to do it even this day, the day of His birth. All considered, there is more in venimus than shews at the first sight. It was not for nothing it was said in the first verse, ecce venerunt; their coming hath an ecce on it, it well deserves it. [257/258]And we, what should we have done? Sure these men of the East will rise in judgment against the men of the West, that is with us, and their faith against ours in this point. With them it was but vidimus, venimus; with us it would have been but veniemus at most. Our fashion is to see and see again before we stir a foot, specially if it be to the worship of Christ. Come such a journey at such a time? No; but fairly have put it off to the spring of the year, till the days longer, and the ways fairer, and the weather warmer, till better travelling to Christ. Our Epiphany would sure have fallen in Easter week at the soonest.But then for the distance, desolateness, tediousness, and the rest, any of them were enough to mar our venimus quite. It must be no great way, first we must come; we love not that. Well fare the shepherds, yet they came but hard by; rather like them than the Magi. Nay, not like them neither. For with us the nearer, lightly the farther off; our proverb is you know, Ôthe nearer the Church, the farther from God.ÕNor it must not be through no desert, over no Petr¾a. If rugged or uneven the way, if the weather ill-disposed, if any so little danger, it is enough to stay us. To Christ we cannot travel, but weather and way and all must be fair. If not, no journey, but still and see farther. As indeed, all our religion is rather vidimus, a contemplation, than venimus, a motion, or stirring to do ought.But when we do it, we must be allowed leisure. Ever veniemus, never venimus; ever coming, never come. We love to make no great haste. To other things perhaps not adorare, the place of the worship of God. Why should we? Christ is no wild-cat. What talk ye of twelve days? And if it be forty days hence, ye shall be sure to find His Mother and Him; she cannot be churched till then. What needs such haste? The truth is, we conceit Him and His birth but slenderly, and our haste is even thereafter. But if we be at that point, we must be out of this venimus; they like enough to leave us behind. Best get us a new Christmas in September; we are not like to come to Christ at this feast. Enough for venimus.But what is venimus without invenimus? And when they come, they hit not on Him at first. No more must we think, [258/259] as soon as ever we be come, to find Him straight. They are fain to come to their ubi est? We must now look back to that. For though it stand before they came, and came before they asked; asked before they found, and found before they worshipped. Between venimus, Ôtheir coming,Õ and adorare, Ôtheir worshipping,Õ there is the true place of dicentes, ubi est?Where, first, we note a double use of their dicentes, these wise men had. 1. As to manifest what they knew, natus est, Ôthat He is born,Õ so to confess and ask what they knew not, the place where. We to have the like.2. Secondly, set down this; that to find where He is, we must learn to ask where He is, which we full little set ourselves to do. If we stumble on Him, so it is; but for any asking we trouble not ourselves, but sit still as we say, and let nature work; and so let grace too, and so for us it shall.I wot well, it is said in a place of Esay, ÔHe was found,Õ a non qu¾rentibus, Ôof some that sought Him not,Õ never asked ubi est But it is no good holding by that place. It was their good hap that so did. But trust not to do it, it is not everybody's case, that. It is better advice you shall read in the Psalm, h¾c est generatio qu¾rentium, Ôthere is a generation of them that seek Him.Õ Of which these were, and of that generation let us be. Regularly there is no promise of invenietis but to quaerite, of finding but to such as Ôseek.Õ It is not safe to presume to find Him otherwise.I thought there had been small use now of ubi est? Yet there is except we hold the ubiquity, that is ubi non, Ôany where.Õ But He is not so. Christ has His ubi, His proper place where He is to be found; and if you miss of that, you miss of Him. And well may we miss, says Christ Himself, there are so many will take upon them to tell us where, and tell us of so many ubis. Ecce h”c. ÔLook you. here He is;Õ Nay, in penetralibis, Ôin such a privy conventicleÕ you shall be sure of Him. And yet He, saith He Himself, in one of them all. There is then yet place for ubi est? I speak not of His natural body, but of His mysticalÑthat is Christ too.How shall we then do? Where shall we get this ÔwhereÕ [259/260] resolved? Where these did. They said it to many, and oft, but got not answer, till they had got together a convocation of Scribes, and they resolved them of Christ's ubi. For they in the East were nothing so wise, or well seen, as we in the West are now grown. We need call no Scribes together, and get them tell us, Ôwhere.Õ Every artisan hath a whole Synod of Scribes in his brain, and can tell where Christ is better than any learned man of them all. Yet these were wise men; best learn where they did.And how did the Scribes resolve it them? Out of Micah. As before to the star they join Balaam's prophecy, so now again to His orietur, that such a one should be born, they had put Micah's et tu Bethlehem, the place of His birth. Still helping, and giving light as it were to the light of Heaven, by a more clear light, the light of the Sanctuary.Thus then to do. And to do it ourselves, and not seek Christ per alium; set others about it as Herod did these, and sit still ourselves. For so, we may hap never find Him no more than he did.And now we have found Ôwhere,Õ what then? It is neither in seeking nor finding, venimus nor invenimus; the end of all, the cause of all is in the last words, adorare Eum, Ôto worship Him.Õ That is all in all, and without it all our seeing, coming, seeking and finding is to no purpose. The Scribes they could tell, and did tell where He was, but were never the nearer for it, for they worshipped Him not. For this end to seek Him.This is acknowledged: Herod, in effect, said as much. He would know where He were fain, and if they will bring him word where, he will come too and worship Him, that He will. None of that worship. If he find Him, his worshipping will prove worrying; as did appear by a sort of silly poor lambs that he worried, when he could not have his will on Christ. Thus he at His birth.And at His death, the other Herod, he sought Him too; but it was that he and his soldiers might make themselves sport with Him. Such seeking there is otherwhile. And such worshipping; as they in the judgment-hall worshipped Him with Ave Rex, and then gave Him a bob blindfold. The world's worship of Him for the most part. [260/261]But we may be bold to say, Herod was Ôa fox.Õ These mean as they say; to worship Him they come, and worship Him they will. Will they so? Be they well advised what they promise, before they know whether they shall find Him in a worshipful taking or no? For full little know they, where and in what case they shall find Him. What, if in a stable, laid there in a manger, and the rest suitable to it; in as poor and pitiful a plight as ever was any, more like to be abhorred than adored of such persons? Will they be as good as their word, trow? Will they not step back at the sight, repent themselves of their journey, and wish themselves at home again? But so find Him, and so finding Him, worship Him for all that? If they will, verily then great is their faith. This, the clearest beam of all.ÔThe Queen of the South,Õ who was a figure of these Kings of the East, she came as great a journey as these. But when she came, she found a King indeed, King Solomon in all his royalty. Saw a glorious King, and a glorious court about him. Saw, him, and heard him; tried him with many hard questions, received satisfaction of them all. This was worth her coming. Weigh what she found, and what these hereÑas poor and unlikely a birth as could be, ever to prove a King, or any great matter. No sight to comfort them, nor a word for which they any wit the wiser; nothing worth their travel. Weigh these together, and great odds will be found between her faith and theirs. Theirs the greater far.Well, they will take Him as they find Him, and all this notwithstanding, worship Him for all that. The Star shall make amends for the manger, and for stella Ejus they will dispense with Eum.And what is it to worship? Some great matter sure it is, that Heaven and earth, the stars and Prophets, thus do but serve to lead them and conduct us to. For all we see ends in adorare. Scriptura et mundud as hoc sunt, ut colatur Qui creavit, et adoretur Qui inspiravit; Ôthe Scripture and world are but to this end, that He That created the one and inspired the other might be but worshipped.Õ Such reckoning did these seem to make of it here. And such the great treasurer of the Queen Candace. These came from the mountains in the East; he from the uttermost part of ®thiopia came, [261/262] and came for no other end but only thisÑto worship; and when they had done that, home again. Tanti est adorare. Worth the while, worth our coming, if coming we do but that, but worship and nothing else. And so I would have men account of it.To tell you what it in particular, I must put you over to the eleventh verse, where it is set down what they did when they worshipped. It is set down in two acts proskneÜn, and prosfùrein, Ôfalling down,Õ and Ôoffering.Õ Thus did they, thus we to do; we to do the like when we will worship. These two are all and more than these we find not.We can worship God but three ways: we have but three things to worship Him withal. 1. The soul He hath inspired; 2. the body He hath ordained us; 3. and the worldly goods He hath vouchsafed to bless us withal. We to worship Him with all, seeing there is but one reason for all.If He breathed into us our soul, but framed not our body, but some other did that, neither bow your knee nor uncover your head, but keep on your hats, and sit even as you do hardly. But if He hath framed that body of yours and every member of it, let Him have the honour both of head and knee, and every member else.Again, if it be not He That gave us our wordly goods but somebody else, what He gave not, that withhold from Him and spare not. But if all come from Him, all to return to Him. If He send all, to be worshipped with all. And this in good sooth is but rationabile obsequium, as the Apostle calleth it. No more than reason would, we should worship Him with all.If all our worship be inward only, with our hearts and not our hats as some fondly imagine, we give Him but one of three; we put Him to His thirds, bid Him be content with that, He get no more but inward worship. That is out of the text quite. For though I doubt not but these here performed that also, yet here it is not. St. Matthew mentions it not, it is not to be seen, no vidimus on it. And the text is a vidimus, and of a star; that is, of an outward visible worship to be seen of all. There is a vidimus upon the worship of the body, it may be seenÑprocidentes. Let us see you fall down. So is there upon the worship with our worldly goods, [262/263] that may be seen and felt offerentes. Let us see whether and what you offer. With both which, no less than with the soul God is to be worshipped. ÔGlorify God with your bodies, for they are God's,Õ saith the Apostle. ÔHonour God with your substance, for He hath blessed your store,Õ saith Solomon. It is the precept of a wise King, of one there; it is the practice of more than one, of these three here. Specially now; for Christ hath now a body, for which to do Him worship with our bodies. And now He was made poor to make us rich, and so offerentes will do well, comes very fit.To enter farther into these two would be too long, and indeed they be not in our verse here, and so for some other treatise at some other time.There now remains nothing but to include ourselves, and bear our part with them, and with the angels, and all who this day adored Him.This was the loadstar of the Magi, and what were they? Gentiles. So are we. But it if must be ours, then we are to go with them; vade, et fac similiter, Ôgo, and do thou likewise.Õ It is Stella gentium, but idem agentium Ôthe Gentiles' star,Õ but Ôsuch Gentiles as overtake these and keep company with them.Õ In their dicentes, Ôconfessing their faith freely;Õ in their vidimus, Ôgrounding it throughly;Õ in their venimus, Ôhasting to come to Him speedily;Õ in their ubi est Ôenquiring Him out diligently;Õ and in their adorare um, Ôworshipping Him devoutly.Õ Per omnia doing as these did; worshipping and thus worshipping, celebrating and thus celebrating the feast of His birth.We cannot say vidimus stellam; the star is gone long since, not now to be seen. Yet I hope for all that, that venimus adorare, Ôwe be come thither to worship.Õ It will be more acceptable, if not seeing it we worship though. It is enough we read of it in the text; we see it there. And indeed as I said, it skills not for the star in the firmament, if the same day-star be risen in our hearts that was in theirs, and the same beams of it to be seen, all five. For then we have our part in it no less, nay full out as much as they. It will bring us whither it brought them, to Christ, Who at His second appearing in glory will call forth these wise men, and all who have ensued the steps of their faith, and that upon the reason [263/264] specified in the text; for I have seen their star shining and showing forth itself by the like beams; and as they came to worship Me, so am I come to do them worship. A venite then, for a venimus now. Their star I have seen, and give them a place above among the stars. They fell down; I will lift them up and exalt them. And as they offered to Me, so I am come to bestow on them, and to reward them with endless joy and bliss on My heavenly Kingdom. To which, &c.

Project Canterbury

During the reign of James I[edit]

Andrewes' name is the first on the list of divines appointed to compile the Authorized Version of the Bible. He headed the "First Westminster Company" which took charge of the first books of the Old Testament (Genesis to 2 Kings). He acted, furthermore, as a sort of general editor for the project as well.

On 31 October 1605 his election as Bishop of Chichester was confirmed, he was consecrated a bishop on 3 November, installed at Chichester Cathedral on 18 November[3] and made Lord High Almoner (until 1619).[5] Following the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot Andrewes was asked to prepare a sermon to be presented to the king in 1606 (Sermons Preached upon the V of November, in Lancelot Andrewes, XCVI Sermons, 3rd. Edition (London,1635) pp. 889,890, 900-1008 ). In this sermon Lancelot Andrewes justified the need to commemorate the deliverance and defined the nature of celebrations. This sermon became the foundation of celebrations which continue 400 years later.[6] In 1609 he published Tortura Torti, a learned work which grew out of the Gunpowder Plot controversy and was written in answer to Bellarmine's Matthaeus Tortus, which attacked James I's book on the oath of allegiance. After moving to Ely[3] (his election to that See was confirmed on 22 September),[5] he again controverted Bellarmine in the Responsio ad Apologiam.

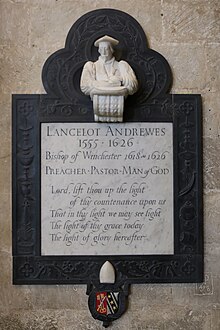

In 1617 he accompanied James I to Scotland with a view to persuading the Scots that Episcopacy was preferable to Presbyterianism. He was made dean of the Chapel Royal and translated (by the confirmation of his election to that See in February 1619)[5] to Winchester, a diocese that he administered with great success. Following his death in 1626 in his Southwark palace, he was mourned alike by leaders in Church and state, and buried beside the high altar in St Saviour's (now Southwark Cathedral, then in the Diocese of Winchester).

Legacy[edit]

-

- This reverend shadow cast that setting sun,

- Whose glorious course through our horizon run,

- Left the dim face of this dull hemisphere,

- All one great eye, all drown'd in one great teare.

As to the Real Presence we are agreed; our controversy is as to the mode of it. As to the mode we define nothing rashly, nor anxiously investigate, any more than in the Incarnation of Christ we ask how the human is united to the divine nature in One Person. There is a real change in the elements—we allow ut panis iam consecratus non sit panis quem natura formavit; sed, quem benedictio consecravit, et consecrando etiam immutavit. (Responsio, p. 263).

Adoration is permitted, and the use of the terms "sacrifice" and "altar" maintained as being consonant with scripture and antiquity. Christ is "a sacrifice—so, to be slain; a propitiatory sacrifice—so, to be eaten." (Sermons, vol. ii. p. 296).

By the same rules that the Passover was, by the same may ours be termed a sacrifice. In rigour of speech, neither of them; for to speak after the exact manner of divinity, there is but one only sacrifice, veri nominis, that is Christ's death. And that sacrifice but once actually performed at His death, but ever before represented in figure, from the beginning; and ever since repeated in memory to the world's end. That only absolute, all else relative to it, representative of it, operative by it ... Hence it is that what names theirs carried, ours do the like, and the Fathers make no scruple at it—no more need we.(Sermons, vol. ii. p. 300).

His Life was written by Whyte (Edinburgh, 1896), M. Wood (New York, 1898), and Ottley (Boston, 1894). His services to his church have been summed up thus: (1) he has a keen sense of the proportion of the faith and maintains a clear distinction between what is fundamental, needing ecclesiastical commands, and subsidiary, needing only ecclesiastical guidance and suggestion; (2) as distinguished from the earlier protesting standpoint, e.g. of the Thirty-nine Articles, he emphasized a positive and constructive statement of the Anglican position.

His best-known work is the Preces Privatae or Private Prayers, edited by Alexander Whyte (1896),[7] which has widespread appeal and has remained in print since renewed interest in Andrewes developed in the 19th century. The Preces Privatae were first published by R. Drake in 1648; an improved edition by F. E. Brightman appeared in 1903.[8] Andrewes's other works occupy eight volumes in the Library of Anglo-Catholic Theology (1841 – 1854). Ninety-six of his sermons were published in 1631 by command of King Charles I, have been occasionally reprinted, and are considered among the most rhetorically developed and polished sermons of the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries. Because of these, Andrewes has been commemorated by literary greats such as T. S. Eliot. https://www.poetryarchive.org/explore/browsepoems?f[0]=sm_field_poet:node:192462 https://www.poetryarchive.org/poem/journey-magi

Andrewes was considered, next to Ussher, to be the most learned churchman of his day, and enjoyed a great reputation as an eloquent and impassioned preacher, but the stiffness and artificiality of his style render his sermons unsuited to modern taste. Nevertheless, there are passages of extraordinary beauty and profundity. His doctrine was High Church, and in his life he was humble, pious, and charitable. He continues to influence religious thinkers to the present day, and was cited as an influence by T. S. Eliot, among others. Eliot also borrowed, almost word for word and without his usual acknowledgement, a passage from Andrewes' 1622 Christmas Day sermon for the opening of his poem "Journey of the Magi". In his 1997 novel Timequake, Kurt Vonnegut suggested that Andrewes was "the greatest writer in the English language," citing as proof the first few verses of the 23rd Psalm. His translation work has also led him to appear as a character in three plays dealing with the King James Bible, Howard Brenton's Anne Boleyn (2010), Jonathan Holmes' Into Thy Hands (2011) and David Edgar's Written on the Heart (2011).

He has an academic cap named after him, known as the Bishop Andrewes cap, which is like a mortarboard but made of velvet, floppy and has a tump or tuff instead of a tassel. This was in fact the ancient version of the mortarboard before the top square was stiffened and the tump replaced by a tassel and button. This cap is still used by Cambridge DDs and at certain institutions as part of their academic dress.

Styles and titles[edit]

- 1555–c. 1579: Lancelot Andrewes Esq.

- c. 1579–1589: The Reverend Lancelot Andrewes

- 1589–bef. 1590: The Reverend Prebendary Lancelot Andrewes

- bef. 1590–1594: The Reverend Prebendary Doctor Lancelot Andrewes

- 1594–1601: The Reverend Canon Doctor Lancelot Andrewes

- 1601–1605: The Very Reverend Doctor Lancelot Andrewes

- 1605–1626: The Right Reverend Doctor Lancelot Andrewes

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ "Andrews, Lancelot (ANDS571L)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Jump up ^ Allen 1998, pp. 116-117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Persons: Andrewes, Lancelot (1580–1609) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 1 February 2014)

- Jump up ^ M'Clure 1853, p. 78.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Andrewes, Lancelot". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/520. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Jump up ^ Andrewes 1606.

- Jump up ^ Whyte 1896.

- Jump up ^ Cross 1957, p. 50.

Sources[edit]

- Andrewes, Lancelot (1606).

Gunpowder Plot Sermon. Wikisource.

Gunpowder Plot Sermon. Wikisource. - Cross, Frank Leslie (1957). The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press.

- Whyte, Alexander (1896). Lancelot Andrewes and His Private Devotions: A Biography, a Transcript and an Interpretation. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier.

- M'Clure, Alexander Wilson (1853). The Translators Revived: A Biographical Memoir of the Authors of the English Version of the Holy Bible. C. Scribner.

- Allen, Brigid (1998). "The Early History of Jesus College, Oxford 1571 – 1603" (PDF). Oxoniensia. LXIII: 116–117. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns (1928). For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays on Style and Order. London: Faber & Gwyer.

- Frere, Walter Howard (1899), "Lancelot Andrewes as a Representative of Anglican Principles: A Lecture Delivered at Holy Trinity, Chelsea, February 28, 1897", Church Historical Society, S.P.C.K., 44

- Higham, Florence May Greir Evans (1952). Lancelot Andrewes. Winchester: Morehouse-Gorham.

- Isaacson, Henry (1650). An Exact Narration of the Life and Death of the Reverend and Learned Prelate and Painful Divine, Lancelot Andrewes, Late Bishop of Winchester. neer S. Brides church, Fleetstreet: John Stafford,.

- Ottley, Robert L. (1894). Lancelot Andrewes. London: Methuen & Company.

- Lancelot Andrewes bibliography maintained by William S. Peterson

- Russell, Arthur Tozer (1860). Memoirs of the life and works of Lancelot Andrewes. Cambridge: J. Palmer.

- Welsby, Paul Antony (1964). Lancelot Andrewes: 1555 - 1626. S.P.C.K.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Andrewes, Lancelot". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Andrewes, Lancelot". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Andrewes, Lancelot". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Andrewes, Lancelot". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

External links[edit]

- Bishops: Andrewes, Lancelot (Bishop of Chichester) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 1 February 2014)

- Bishops: Andrewes, Lancelot (Bishop of Ely) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 1 February 2014)

- Bishops: Andrewes, Lancelot (Bishop of Winchester) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 1 February 2014)

- Lancelot Andrewes (1555–1626) by Dr Marianne Dorman

- Lancelot Andrewes on Project Canterbury

- Works by Lancelot Andrewes at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- The Gunpowder Plot Sermon

- Works by or about Lancelot Andrewes at Internet Archive

- Works by Lancelot Andrewes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Fulke | Master of Pembroke College, Cambridge 1589–1605 | Succeeded by Samuel Harsnett |

| Church of England titles | ||

| Preceded by Anthony Watson | Bishop of Chichester 1605–1609 | Succeeded by Samuel Harsnett |

| Preceded by Martin Heton | Bishop of Ely 1609–1619 | Succeeded by Nicholas Felton |

| Preceded by James Montague | Bishop of Winchester 1618–1626 | Succeeded by Richard Neile |

No comments:

Post a Comment